Back John Locke AF John Locke ALS ጆን ሎክ AM John Locke AN John Locke ANG جون لوك Arabic دجون لوك ARY جون لوك ARZ John Locke AST Con Lokk AZ

John Locke | |

|---|---|

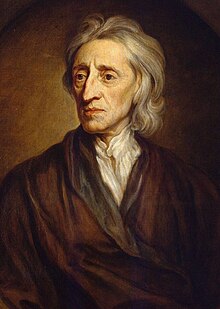

Portrait of Locke, 1697 | |

| Born | John Locke 29 August 1632 |

| Died | 28 October 1704 (aged 72) High Laver, Essex, England |

| Education | Christ Church, Oxford (BA, 1656; MA, 1658; MB, 1675) |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | University of Oxford[7] Royal Society |

Main interests | Metaphysics, epistemology, political philosophy, philosophy of mind, philosophy of education, economics |

Notable ideas | List

|

| Signature | |

| |

|

| Part of a series on |

| John Locke |

|---|

|

Works (listed chronologically) |

| People |

| Related topics |

John Locke (/lɒk/; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism".[11][12][13] Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, Locke is equally important to social contract theory. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American Revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence.[14] Internationally, Locke's political-legal principles continue to have a profound influence on the theory and practice of limited representative government and the protection of basic rights and freedoms under the rule of law.[15]

Locke's theory of mind is often cited as the origin of modern conceptions of identity and the self, figuring prominently in the work of later philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant.

He postulated that, at birth, the mind was a blank slate, or tabula rasa. Contrary to Cartesian philosophy based on pre-existing concepts, he maintained that we are born without innate ideas, and that knowledge is instead determined only by experience derived from sense perception, a concept now known as empiricism.[16]

- ^ Fumerton, Richard (2000). "Foundationalist Theories of Epistemic Justification". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ David Bostock (2009). Philosophy of Mathematics: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 43.

All of Descartes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume supposed that mathematics is a theory of our ideas, but none of them offered any argument for this conceptualist claim, and apparently took it to be uncontroversial.

- ^ John W. Yolton (2000). Realism and Appearances: An Essay in Ontology. Cambridge University Press. p. 136.

- ^ "The Correspondence Theory of Truth". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Grigoris Antoniou; John Slaney, eds. (1998). Advanced Topics in Artificial Intelligence. Springer. p. 9.

- ^ Vere Claiborne Chappell, ed. (1994). The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge University Press. p. 56.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

sepwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hansen, Hans V.; Pinto, Robert C., eds. (1995). Fallacies: classical and contemporary readings. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01416-6. OCLC 30624864.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). "Book IV, Chapter XVII: Of Reason". An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). Two Treatises of Government (10th ed.): Chapter II, Section 6. Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Hirschmann, Nancy J. (2009). Gender, Class, and Freedom in Modern Political Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 79.

- ^ Sharma, Urmila; S. K. Sharma (2006). Western Political Thought. Washington: Atlantic Publishers. p. 440.

- ^ Korab-Karpowicz, W. Julian (2010). A History of Political Philosophy: From Thucydides to Locke. New York: Global Scholarly Publications. p. 291.

- ^ Becker, Carl Lotus (1922). The Declaration of Independence: a Study in the History of Political Ideas. New York: Harcourt, Brace. p. 27.

- ^ "Foreword and study guide to" John Locke's Two Treatises on Government: A Translation into Modern English, ISR Publications, 2013, p. ii. ISBN 978-0906321690

- ^ Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 527–529. ISBN 978-0-13-158591-1.