Back Godheid AF देवता ANP إله Arabic رب ARY İlah AZ Dievībė BAT-SMG Бажаство BE Божество Bulgarian দেবতা Bengali/Bangla Deïtat Catalan

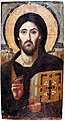

A deity or god is a supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to having authority over the universe, nature or human life.[1][2] The Oxford Dictionary of English defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine.[3] C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater than those of ordinary humans, but who interacts with humans, positively or negatively, in ways that carry humans to new levels of consciousness, beyond the grounded preoccupations of ordinary life".[4]

Religions can be categorized by how many deities they worship. Monotheistic religions accept only one deity (predominantly referred to as "God"),[5][6] whereas polytheistic religions accept multiple deities.[7] Henotheistic religions accept one supreme deity without denying other deities, considering them as aspects of the same divine principle.[8][9] Nontheistic religions deny any supreme eternal creator deity, but may accept a pantheon of deities which live, die and may be reborn like any other being.[10]: 35–37 [11]: 357–358

Although most monotheistic religions traditionally envision their god as omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent, and eternal,[12][13] none of these qualities are essential to the definition of a "deity"[14][15][16] and various cultures have conceptualized their deities differently.[14][15] Monotheistic religions typically refer to their god in masculine terms,[17][18]: 96 while other religions refer to their deities in a variety of ways—male, female, hermaphroditic, or genderless.[19][20][21]

Many cultures—including the ancient Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Germanic peoples—have personified natural phenomena, variously as either deliberate causes or effects.[22][23][24] Some Avestan and Vedic deities were viewed as ethical concepts.[22][23] In Indian religions, deities have been envisioned as manifesting within the temple of every living being's body, as sensory organs and mind.[25][26][27] Deities are envisioned as a form of existence (Saṃsāra) after rebirth, for human beings who gain merit through an ethical life, where they become guardian deities and live blissfully in heaven, but are also subject to death when their merit is lost.[10]: 35–38 [11]: 356–359

- ^ "god". Cambridge Dictionary.

- ^ "Definition of GOD". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Littleton, C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology. New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-7614-7559-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Becking, Bob; Dijkstra, Meindert; Korpel, Marjo; Vriezen, Karel (2001). Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. London: New York. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-567-23212-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

The Christian tradition is, in imitation of Judaism, a monotheistic religion. This implies that believers accept the existence of only one God. Other deities either do not exist, are considered inferior, are seen as the product of human imagination, or are dismissed as remnants of a persistent paganism

- ^ Korte, Anne-Marie; Haardt, Maaike De (2009). The Boundaries of Monotheism: Interdisciplinary Explorations Into the Foundations of Western Monotheism. Brill. p. 9. ISBN 978-90-04-17316-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Brown, Jeannine K. (2007). Scripture as Communication: Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics. Baker Academic. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8010-2788-8. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Harrison, Victoria S.; Goetz, Stewart (2012). The Routledge Companion to Theism. Routledge. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-136-33823-6. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Reat, N. Ross; Perry, Edmund F. (1991). A World Theology: The Central Spiritual Reality of Humankind. Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-0-521-33159-3. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Keownwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Bullivantwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Taliaferro, Charles; Marty, Elsa J. (2010). A Dictionary of Philosophy of Religion. A&C Black. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-1-4411-1197-5.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 473–474. ISBN 978-0-521-82245-9.

- ^ a b Hood, Robert Earl (1990). Must God Remain Greek?: Afro Cultures and God-talk. Fortress Press. pp. 128–29. ISBN 978-1-4514-1726-5.

African people may describe their deities as strong, but not omnipotent; wise but not omniscient; old but not eternal; great but not omnipresent (...)

- ^ a b Trigger, Bruce G. (2003). Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 441–42. ISBN 978-0-521-82245-9.

[Historically...] people perceived far fewer differences between themselves and the gods than the adherents of modern monotheistic religions. Deities were not thought to be omniscient or omnipotent and were rarely believed to be changeless or eternal

- ^ Murdoch, John (1861). English Translations of Select Tracts, Published in India: With an Introd. Containing Lists of the Tracts in Each Language. Graves. pp. 141–42.

We [monotheists] find by reason and revelation that God is omniscient, omnipotent, most holy, etc., but the Hindu deities possess none of those attributes. It is mentioned in their Shastras that their deities were all vanquished by the Asurs, while they fought in the heavens, and for fear of whom they left their abodes. This plainly shows that they are not omnipotent.

- ^ Kramarae, Cheris; Spender, Dale (2004). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women's Issues and Knowledge. Routledge. p. 655. ISBN 978-1-135-96315-6. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

OBrien2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bonnefoy, Yves (1992). Roman and European Mythologies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 274–75. ISBN 978-0-226-06455-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Pintchman, Tracy (2014). Seeking Mahadevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess. SUNY Press. pp. 1–2, 19–20. ISBN 978-0-7914-9049-5. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Nathaniel (2016). To Be Cared For: The Power of Conversion and Foreignness of Belonging in an Indian Slum. University of California Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-520-96363-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Malandra, William W. (1983). An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion: Readings from the Avesta and the Achaemenid Inscriptions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-8166-1115-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Fløistad, Guttorm (2010). Volume 10: Philosophy of Religion (1st ed.). Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media B.V. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-90-481-3527-1. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Potts, Daniel T. (1997). Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations (st ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 272–274. ISBN 978-0-8014-3339-9. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Potter, Karl H. (2014). The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 3: Advaita Vedanta up to Samkara and His Pupils. Princeton University Press. pp. 272–74. ISBN 978-1-4008-5651-0. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (2006). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Cush, Denise; Robinson, Catherine; York, Michael (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. London: Routledge. pp. 899–900. ISBN 978-1-135-18979-2. Retrieved 28 June 2017.