Back Kanker AF Krebs (Medizin) ALS ካንሰር AM Cáncer AN कर्कट रोग ANP سرطان Arabic ܬܠܗܝܐ ARC سرطان ARZ কৰ্কট ৰোগ AS Cáncanu AST

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (March 2024) |

| Cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Malignant tumor, malignant neoplasm |

| |

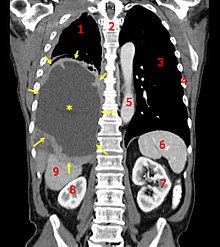

| A coronal CT scan showing a malignant mesothelioma Legend: → tumor ←, ✱ central pleural effusion, 1 & 3 lungs, 2 spine, 4 ribs, 5 aorta, 6 spleen, 7 & 8 kidneys, 9 liver | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Lump, abnormal bleeding, prolonged cough, unexplained weight loss, change in bowel movements[1] |

| Risk factors | Exposure to carcinogens, tobacco, obesity, poor diet, lack of physical activity, excessive alcohol, certain infections[2][3] |

| Treatment | Radiation therapy, surgery, chemotherapy, targeted therapy[2][4] |

| Prognosis | Average five-year survival 66% (USA)[5] |

| Frequency | 24 million annually (2019)[6] |

| Deaths | 10 million annually (2019)[6] |

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.[2][7] These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread.[7] Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bleeding, prolonged cough, unexplained weight loss, and a change in bowel movements.[1] While these symptoms may indicate cancer, they can also have other causes.[1] Over 100 types of cancers affect humans.[7]

Tobacco use is the cause of about 22% of cancer deaths.[2] Another 10% are due to obesity, poor diet, lack of physical activity or excessive alcohol consumption.[2][8][9] Other factors include certain infections, exposure to ionizing radiation, and environmental pollutants.[3] Infection with specific viruses, bacteria and parasites is an environmental factor causing approximately 16-18% of cancers worldwide.[10] These infectious agents include Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human papillomavirus infection, Epstein–Barr virus, Human T-lymphotropic virus 1, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and Merkel cell polyomavirus. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) does not directly cause cancer but it causes immune deficiency that can magnify the risk due to other infections, sometimes up to several thousand fold (in the case of Kaposi's sarcoma). Importantly, vaccination against hepatitis B and human papillomavirus have been shown to nearly eliminate risk of cancers caused by these viruses in persons successfully vaccinated prior to infection.

These environmental factors act, at least partly, by changing the genes of a cell.[11] Typically, many genetic changes are required before cancer develops.[11] Approximately 5–10% of cancers are due to inherited genetic defects.[12] Cancer can be detected by certain signs and symptoms or screening tests.[2] It is then typically further investigated by medical imaging and confirmed by biopsy.[13]

The risk of developing certain cancers can be reduced by not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, limiting alcohol intake, eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, vaccination against certain infectious diseases, limiting consumption of processed meat and red meat, and limiting exposure to direct sunlight.[14][15] Early detection through screening is useful for cervical and colorectal cancer.[16] The benefits of screening for breast cancer are controversial.[16][17] Cancer is often treated with some combination of radiation therapy, surgery, chemotherapy and targeted therapy.[2][4] Pain and symptom management are an important part of care.[2] Palliative care is particularly important in people with advanced disease.[2] The chance of survival depends on the type of cancer and extent of disease at the start of treatment.[11] In children under 15 at diagnosis, the five-year survival rate in the developed world is on average 80%.[18] For cancer in the United States, the average five-year survival rate is 66% for all ages.[5]

In 2015, about 90.5 million people worldwide had cancer.[19] In 2019, annual cancer cases grew by 23.6 million people, and there were 10 million deaths worldwide, representing over the previous decade increases of 26% and 21%, respectively.[6][20]

The most common types of cancer in males are lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and stomach cancer.[21][22] In females, the most common types are breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and cervical cancer.[11][22] If skin cancer other than melanoma were included in total new cancer cases each year, it would account for around 40% of cases.[23][24] In children, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and brain tumors are most common, except in Africa, where non-Hodgkin lymphoma occurs more often.[18] In 2012, about 165,000 children under 15 years of age were diagnosed with cancer.[21] The risk of cancer increases significantly with age, and many cancers occur more commonly in developed countries.[11] Rates are increasing as more people live to an old age and as lifestyle changes occur in the developing world.[25] The global total economic costs of cancer were estimated at US$1.16 trillion (equivalent to $1.62 trillion in 2023) per year as of 2010[update].[26]

- ^ a b c "Cancer – Signs and symptoms". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Cancer". World Health Organization. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ a b Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Lai OS, Sung B, Aggarwal BB (September 2008). "Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes". Pharmaceutical Research. 25 (9): 2097–116. doi:10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9. PMC 2515569. PMID 18626751.

- ^ a b "Targeted Cancer Therapies". cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: All Cancer Sites". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ^ a b c Kocarnik, JM; others (2022). "Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019. A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019". JAMA Oncology. 8 (3): 420–444. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6987. PMC 8719276. PMID 34967848.

- ^ a b c "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Obesity and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 3 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Jayasekara H, MacInnis RJ, Room R, English DR (May 2016). "Long-Term Alcohol Consumption and Breast, Upper Aero-Digestive Tract and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 51 (3): 315–30. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv110. PMID 26400678.

- ^ "Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis – The Lancet Global Health".

- ^ a b c d e World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017.

- ^ "Heredity and Cancer". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "How is cancer diagnosed?". American Cancer Society. 29 January 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bandera EV, Gapstur S, Patel AV, Andrews K, Gansler T (2012). "American Cancer Society Guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 62 (1): 30–67. doi:10.3322/caac.20140. PMID 22237782. S2CID 2067308.

- ^ Parkin DM, Boyd L, Walker LC (December 2011). "16. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010". British Journal of Cancer. 105 (Suppl 2): S77–81. doi:10.1038/bjc.2011.489. PMC 3252065. PMID 22158327.

- ^ a b World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 4.7. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017.

- ^ Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ (June 2013). "Screening for breast cancer with mammography". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD001877. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5. PMC 6464778. PMID 23737396.

- ^ a b World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.3. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017.

- ^ GBD; et al. (Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Sciacovelli M, Schmidt C, Maher ER, Frezza C (2020). "Metabolic Drivers in Hereditary Cancer Syndromes". Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 4: 77–97. doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033612.

- ^ a b World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9.

- ^ a b Siegel, Rebecca L.; Miller, Kimberly D.; Wagle, Nikita Sandeep; Jemal, Ahmedin (January 2023). "Cancer statistics, 2023". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 73 (1): 17–48. doi:10.3322/caac.21763. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 36633525.

- ^ Dubas LE, Ingraffea A (February 2013). "Nonmelanoma skin cancer". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 21 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2012.10.003. PMID 23369588.

- ^ Cakir BÖ, Adamson P, Cingi C (November 2012). "Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 20 (4): 419–22. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2012.07.004. PMID 23084294.

- ^ Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D (February 2011). "Global cancer statistics". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 61 (2): 69–90. doi:10.3322/caac.20107. PMID 21296855. S2CID 30500384.

- ^ World Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 6.7. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017.