Back Malaria AF Malaria ALS Malaria AN शीतज्वर ANP ملاريا Arabic مالاريا ARZ মেলেৰিয়া AS Malaria AST मलेरिया AWA Malyariya AZ

| Malaria | |

|---|---|

| |

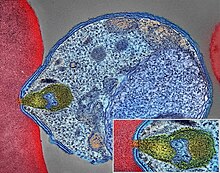

| Malaria parasite connecting to a red blood cell | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, vomiting, headache, yellow skin[1] |

| Complications | seizures, coma,[1] organ failure, anemia, cerebral malaria[2] |

| Usual onset | 10–15 days post exposure[3] |

| Causes | Plasmodium transmitted to humans by Anopheles mosquitoes[1][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Examination of the blood, antigen detection tests[1] |

| Prevention | Mosquito nets, insect repellent, mosquito control, medications[1] |

| Medication | Antimalarial medication[3] |

| Frequency | 247 million (2021)[5] |

| Deaths | 619,000 (2021)[5] |

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other vertebrates.[6][7][3] Human malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, fatigue, vomiting, and headaches.[1][8] In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death.[1] Symptoms usually begin 10 to 15 days after being bitten by an infected Anopheles mosquito.[9][4] If not properly treated, people may have recurrences of the disease months later.[3] In those who have recently survived an infection, reinfection usually causes milder symptoms.[1] This partial resistance disappears over months to years if the person has no continuing exposure to malaria.[1]

Human malaria is caused by single-celled microorganisms of the Plasmodium group.[9] It is spread exclusively through bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.[9][10] The mosquito bite introduces the parasites from the mosquito's saliva into a person's blood.[3] The parasites travel to the liver where they mature and reproduce.[1] Five species of Plasmodium commonly infect humans.[9] The three species associated with more severe cases are P. falciparum (which is responsible for the vast majority of malaria deaths), P. vivax, and P. knowlesi (a simian malaria that spills over into thousands of people a year).[11][12] P. ovale and P. malariae generally cause a milder form of malaria.[1][9] Malaria is typically diagnosed by the microscopic examination of blood using blood films, or with antigen-based rapid diagnostic tests.[1] Methods that use the polymerase chain reaction to detect the parasite's DNA have been developed, but they are not widely used in areas where malaria is common, due to their cost and complexity.[13]

The risk of disease can be reduced by preventing mosquito bites through the use of mosquito nets and insect repellents or with mosquito-control measures such as spraying insecticides and draining standing water.[1] Several medications are available to prevent malaria for travellers in areas where the disease is common.[3] Occasional doses of the combination medication sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine are recommended in infants and after the first trimester of pregnancy in areas with high rates of malaria.[3] As of 2023, two malaria vaccines have been endorsed by the World Health Organization.[14] The recommended treatment for malaria is a combination of antimalarial medications that includes artemisinin.[15][5][1][3] The second medication may be either mefloquine, lumefantrine, or sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine.[16] Quinine, along with doxycycline, may be used if artemisinin is not available.[16] In areas where the disease is common, malaria should be confirmed if possible before treatment is started due to concerns of increasing drug resistance.[3] Resistance among the parasites has developed to several antimalarial medications; for example, chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum has spread to most malarial areas, and resistance to artemisinin has become a problem in some parts of Southeast Asia.[3]

The disease is widespread in the tropical and subtropical regions that exist in a broad band around the equator.[17][1] This includes much of sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America.[3] In 2022, some 249 million cases of malaria worldwide resulted in an estimated 608000 deaths, with 80 percent being five years old or less.[18] Around 95% of the cases and deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. Rates of disease decreased from 2010 to 2014, but increased from 2015 to 2021.[5] According to UNICEF, nearly every minute, a child under five died of malaria in 2021,[19] and "many of these deaths are preventable and treatable".[20] Malaria is commonly associated with poverty and has a significant negative effect on economic development.[21][22] In Africa, it is estimated to result in losses of US$12 billion a year due to increased healthcare costs, lost ability to work, and adverse effects on tourism.[23]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Caraballo H, King K (May 2014). "Emergency department management of mosquito-borne illness: malaria, dengue, and West Nile virus". Emergency Medicine Practice. 16 (5): 1–23, quiz 23–4. PMID 25207355. S2CID 23716674. Archived from the original on 2016-08-01.

- ^ "Malaria". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Malaria Fact sheet N°94". WHO. March 2014. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ a b "CDC - Malaria - FAQs". 28 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d WHO (2022). World Malaria Report 2022. Switzerland: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-006489-8.

- ^ "Vector-borne diseases". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ Dahalan FA, Churcher TS, Windbichler N, Lawniczak MK (November 2019). "The male mosquito contribution towards malaria transmission: Mating influences the Anopheles female midgut transcriptome and increases female susceptibility to human malaria parasites". PLOS Pathogens. 15 (11): e1008063. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1008063. PMC 6837289. PMID 31697788.

- ^ Basu S, Sahi PK (July 2017). "Malaria: An Update". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 84 (7): 521–528. doi:10.1007/s12098-017-2332-2. PMID 28357581. S2CID 11461451.

- ^ a b c d e "Fact sheet about malaria". www.who.int. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Walter K, John CC (February 2022). "Malaria". JAMA. 327 (6): 597. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.21468. PMID 35133414. S2CID 246651569.

- ^ "Fact sheet about malaria". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ World Health Organization. "Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030" (PDF).

- ^ Nadjm B, Behrens RH (June 2012). "Malaria: an update for physicians". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 26 (2): 243–259. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.010. PMID 22632637.

- ^ "WHO recommends R21/Matrix-M vaccine for malaria prevention in updated advice on immunization". 2 October 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Rawat A, Roy M, Jyoti A, Kaushik S, Verma K, Srivastava VK (August 2021). "Cysteine proteases: Battling pathogenic parasitic protozoans with omnipresent enzymes". Microbiological Research. 249: 126784. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2021.126784. PMID 33989978. S2CID 234597200.

- ^ a b Guidelines for the treatment of malaria (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2010. p. ix. ISBN 978-92-4-154792-5.

- ^ Baiden F, Malm KL, Binka F (2021). Malaria. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780198816805.001.0001/med-9780198816805-chapter-73 (inactive 31 January 2024). ISBN 978-0-19-185838-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ "World malaria report 2022". www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ "Malaria in Africa". UNICEF DATA. Retrieved 2023-11-02.

- ^ "Nearly every minute, a child under 5 dies of malaria". UNICEF. February 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

IftSoLwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Worrall 2005was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Greenwood 2005was invoked but never defined (see the help page).