Back Taoïsme AF Daoismus ALS Taoísmo AN ताओ धर्म ANP طاوية Arabic طاوية ARY طاويه ARZ Taoísmu AST Daosizm AZ تائوئیزم AZB

This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (December 2023) |

| Taoism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

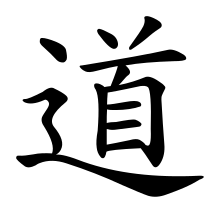

The Chinese character for the Tao, often translated as 'way', 'path', 'technique', or 'doctrine' | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 道教 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Dàojiào | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Religion of the Way" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Đạo giáo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 道教 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 도교 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 道敎 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 道教 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | どうきょう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katakana | ドウキョウ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

Taoism (/ˈdaʊ.ɪzəm/ ⓘ, /ˈtaʊ.ɪzəm/ ⓘ) or Daoism is a diverse tradition indigenous to China, variously characterized as both a philosophy and a religion. Taoism emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao—generally understood as being the impersonal, enigmatic process of transformation ultimately underlying reality.[1][2] The concept originates in the Chinese word 道 (pinyin: dào; Wade–Giles: tao4), which has numerous related meanings: possible English translations include 'way', 'road', and 'technique'. Taoist thought has informed the development of various practices within the Taoist tradition and beyond, including forms of meditation, astrology, qigong, feng shui, and internal alchemy. A common goal of Taoist practice is self-cultivation resulting in a deeper appreciation of the Tao, and thus a more harmonious existence. There are different formulations of Taoist ethics, but there is generally emphasis on virtues such as effortless action, naturalness or spontaneity, simplicity, and the three treasures of compassion, frugality, and humility. Many Taoist terms lack simple definitions and have been translated in several different ways.

The core of Taoist thought crystallized during the early Warring States period, c. the 4th and 5th centuries BCE, during which the epigrammatic Tao Te Ching and the anecdotal Zhuangzi—widely regarded as the fundamental texts of Taoist philosophy—were largely composed. They form the core of a body of Taoist writings accrued over the following centuries, which was assembled by monks into the Daozang canon starting in the 5th century CE. Early Taoism drew upon diverse influences, including the Shang and Zhou state religions, Naturalism, Mohism, Confucianism, various Legalist theories, as well as the Book of Changes and Spring and Autumn Annals.[3][4][5] Later, when Buddhism was introduced to China, the two systems began influencing one another, with long-running discourses shared between Taoists and Buddhists; the distinct Mahayana tradition of Zen that emerged during the Tang dynasty incorporates many ideas from Taoism.

Though Taoism often lacks the motivation for strong hierarchies, Taoist philosophy has often served as a foundation for theories of politics and warfare, and Taoist organizations with diverse agendas have existed throughout Chinese history. During the late Han dynasty, Taoist secret societies precipitated the Yellow Turban Rebellion, attempting to create what has been characterized as a Taoist theocracy. Many denominations of Taoism recognize deities, often those present in other traditions, where they are venerated as superhuman figures exemplifying Taoist virtues. The syncretic nature of the tradition presents particular difficulties in attempting to characterize its practice. Since Taoist thought has been deeply rooted in Chinese culture for millennia, it is often unclear whether one should be considered a "Taoist". The status of daoshi, or 'Taoist master', is traditionally attributed only to clergy in Taoist organizations; these figures usually distinguish between their traditions and others throughout Chinese folk religion.The gods and immortals(神仙) believed in by Taoism can be roughly divided into two categories, namely "gods" and "xian". "Gods" refers to deities, of which there are many kinds. "Xian" were immortal beings with vast supernatural powers, although the word was also used as a descriptor for a principled and moral person.[6]

Today, Taoism is one of five religious doctrines officially recognized by the Chinese government, also having official status in Hong Kong and Macau.[7] It is considered a major religion in Taiwan,[8] and also has significant populations of adherents throughout the Sinosphere and Southeast Asia. In the West, Taoism has taken on diverse forms, both those hewing to historical practice, as well as highly synthesized practices variously characterized as new religious movements.

- ^ Elizabeth Pollard; Clifford Rosenberg; Robert Tignor (16 December 2014). Worlds Together, Worlds Apart: A History of the World – From the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present. W.W. Norton. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Creel (1982), p. 2.

- ^ Kirkland (2004), p. 2-10.

- ^ Kohn (2008), p. 23–33.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Robinet 1997, p. 62was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ 武当山道教协会, 武当山道教协会. "道教神仙分类". Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Religion in China". Council on Foreign Relations. 11 October 2018. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "Taiwan 2017 International Religious Freedom Report". American Institute on Taiwan. US Federal Government. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.