Back فن إسلامي Arabic فن اسلامى ARZ Arte islámicu AST Ісламскае мастацтва BE Ислямско изкуство Bulgarian ইসলামি শিল্প Bengali/Bangla Islamska umjetnost BS Art islàmic Catalan Islámské umění Czech Celf Islamaidd CY

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

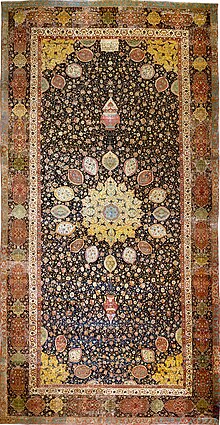

Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations.[1] Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide range of lands, periods, and genres, Islamic art is a concept used first by Western art historians in the late 19th century.[2] Public Islamic art is traditionally non-representational, except for the widespread use of plant forms, usually in varieties of the spiralling arabesque. These are often combined with Islamic calligraphy, geometric patterns in styles that are typically found in a wide variety of media, from small objects in ceramic or metalwork to large decorative schemes in tiling on the outside and inside of large buildings, including mosques. Other forms of Islamic art include Islamic miniature painting, artefacts like Islamic glass or pottery, and textile arts, such as carpets and embroidery.

The early developments of Islamic art were influenced by Roman art, Early Christian art (particularly Byzantine art), and Sassanian art, with later influences from Central Asian nomadic traditions. Chinese art had a significant influence on Islamic painting, pottery, and textiles.[3] From its beginnings, Islamic art has been based on the written version of the Quran and other seminal religious works, which is reflected by the important role of calligraphy, representing the word as the medium of divine revelation.[4][5]

Religious Islamic art has been typically characterized by the absence of figures and extensive use of calligraphic, geometric and abstract floral patterns. In secular art of the Muslim world, representations of human and animal forms historically flourished in nearly all Islamic cultures, although, partly because of opposing religious sentiments, living beings in paintings were often stylized, giving rise to a variety of decorative figural designs.[6]

Both religious and secular art objects often exhibit the same references, styles and forms. These include calligraphy, architecture, textiles and furnishings, such as carpets and woodwork. Secular arts and crafts include the production of textiles, such as clothing, carpets or tents, as well as household objects, made from metal, wood or other materials. Further, figurative miniature paintings have a rich tradition, especially in Persian, Mughal and Ottoman painting. These pictures were often meant to illustrate well-known historical or poetic stories.[7] Some interpretations of Islam, however, include a ban of depiction of animate beings, also known as aniconism. Islamic aniconism stems in part from the prohibition of idolatry and in part from the belief that creation of living forms is God's prerogative.[8][6]

- ^ Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Richard Ettinghausen and Oleg Grabar, 2001, Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4, p.3; Brend, 10

- ^ J. M. Bloom; S. S. Blair (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Vol. II. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^ MSN Encarta: Islamic Art and architecture. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28.

- ^ "Islamic arts | Characteristics, Calligraphy, Paintings, & Architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-10-13.

- ^ Suarez, Michael F. (2010). "38 The History of the Book in the Muslim World". The Oxford companion to the book. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 331ff. ISBN 9780198606536. OCLC 50238944.

- ^ a b "Figural Representation in Islamic Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "One group of painters followed a hedonistic orientation toward a festive representation of events and personages, luxurious ornamentation, and wealth of figures and colors; this is illustrated by the miniatures of the Golestān of 1556-57 and the love scenes by the artist ʿAbdallāh in the Būstān of 1575-76 (...). The other group of miniaturists preferred naive genre scenes illustrating folk characteristics, as in the Toḥfat al-aḥrār of the 1670s." "History of art in Iran. viii. Islamic Central Asia". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2021-10-17.[failed verification]

- ^ Esposito, John L. (2011). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15.