Back አውቶስቴሮግራም AM Autoestereograma Catalan Αυτοστερεόγραμμα Greek Autoestereograma Spanish خودبرجستهنما FA Autostéréogramme French אוטוסטראוגרמה HE Autosztereogram Hungarian Autostereogramma Italian Autostereogram Dutch

)

)

) or wall- (

) or wall- ( ) eyed vergence.

) eyed vergence.An autostereogram is a two-dimensional (2D) image that can create the optical illusion of a three-dimensional (3D) scene. Autostereograms use only one image to accomplish the effect while normal stereograms require two. The 3D scene in an autostereogram is often unrecognizable until it is viewed properly, unlike typical stereograms. Viewing any kind of stereogram properly may cause the viewer to experience vergence-accommodation conflict.

The optical illusion of an autostereogram is one of depth perception and involves stereopsis: depth perception arising from the different perspective each eye has of a three-dimensional scene, called binocular parallax.

Individuals with disordered binocular vision and who cannot perceive depth may require a wiggle stereogram to achieve a similar effect.

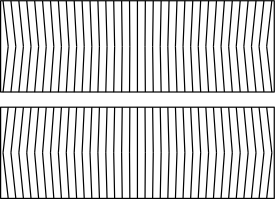

The simplest type of autostereogram consists of a horizontally repeating pattern, with small changes throughout, that looks like wallpaper. When viewed with proper vergence, the repeating patterns appear to float above or below the background. The well-known Magic Eye books feature another type of autostereogram called a random-dot autostereogram , similar to the first example, above. In this type of autostereogram, every pixel in the image is computed from a pattern strip and a depth map. A hidden 3D scene emerges when the image is viewed with the correct vergence.

Unlike normal stereograms, autostereograms do not require the use of a stereoscope. A stereoscope presents 2D images of the same object from slightly different angles to the left eye and the right eye, allowing the viewer to reconstruct the original object via binocular disparity. When viewed with the proper vergence, an autostereogram does the same, the binocular disparity existing in adjacent parts of the repeating 2D patterns.

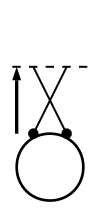

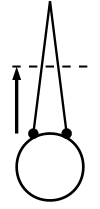

There are two ways an autostereogram can be viewed: wall-eyed and cross-eyed.[a] Most autostereograms (including those in this article) are designed to be viewed in only one way, which is usually wall-eyed. Wall-eyed viewing requires that the two eyes adopt a relatively parallel angle, while cross-eyed viewing requires a relatively convergent angle. An image designed for wall-eyed viewing if viewed correctly will appear to pop out of the background, whereas if viewed cross-eyed it will instead appear as a cut-out behind the background and may be difficult to bring entirely into focus.[b]

- ^ a b c Stephen M. Kosslyn, Daniel N. Osherson (1995). An Invitation to Cognitive Science, 2nd Edition - Vol. 2: Visual Cognition, p. 65 fig. 1.49. ISBN 978-0-262-15042-2.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).