Back عصر إعادة الإعمار Arabic Yenidənqurma dövrü AZ Рэканструкцыя Поўдня BE Reconstrucció (Estats Units) Catalan Rekonstruktionstiden Danish Reconstruction German Rekonstrua Epoko EO Reconstrucción (Estados Unidos) Spanish Rekonstrueerimise ajastu ET دوره بازسازی ایالات متحده آمریکا FA

| Reconstruction era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1865–1877 | |||

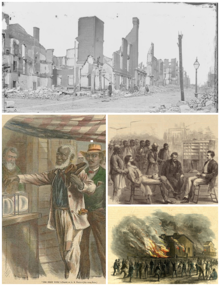

From left to right and up to the bottom: The ruins of Richmond, Virginia; newly-freed African Americans voting for the first time in 1867;[1] office of the Freedmen's Bureau in Memphis, Tennessee; Memphis riots of 1866 | |||

| Location | United States (Southern States) | ||

| Including | Third Party System | ||

| President(s) | Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson Ulysses S. Grant Rutherford B. Hayes | ||

| Key events | Freedmen's Bureau Assassination of Abraham Lincoln Formation of the KKK Reconstruction Acts Impeachment of Andrew Johnson Enforcement Acts Reconstruction Amendments Compromise of 1877 | ||

Chronology

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

The Reconstruction era was a period in United States history following the American Civil War, dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of abolishing slavery and reintegrating the former Confederate States of America into the United States. During this period, three amendments were added to the United States Constitution to grant equal civil rights to the newly freed slaves. Despite this, former Confederate states often used poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation to control people of color.[2]

Starting with the outbreak of war, the Union was confronted with how to administer captured territories and handle the steady stream of slaves escaping to Union lines. In many cases, the United States Army played a vital role in establishing a free labor economy in the South, protecting freedmen's legal rights, and creating educational and religious institutions. Despite reluctance to interfere with the institution of slavery, Congress passed the Confiscation Acts to seize Confederates' slaves, providing the legal basis for President Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Congress later established a Freedmen's Bureau to provide much-needed food and shelter to the newly freed slaves.

As it became clear that the war would end in a Union victory, Congress debated the process for the readmission of seceded states. Radical and moderate Republicans disagreed over the nature of secession, the conditions for readmission, and the desirability of social reforms as a consequence of the Confederate defeat. Lincoln favored the "ten percent plan" and vetoed the radical Wade–Davis Bill, which proposed harsh conditions for readmission. Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, just as fighting was drawing to a close. He was replaced by President Andrew Johnson. Johnson vetoed numerous radical bills, pardoned thousands of Confederate leaders, and allowed Southern states to pass draconian Black Codes that greatly restricted the rights of freedmen. This outraged many Northerners and stoked fears that the South elite would regain its political power. Radical Republican candidates swept the 1866 midterm elections and achieved large majorities in both houses of Congress.

The radical Republicans then took the initiative by passing the Reconstruction Acts in 1867 over Johnson's vetoes, setting out the terms by which they could be readmitted to the Union. Constitutional conventions held throughout the South gave Black men the right to vote. New state governments were established by a coalition of freedmen, supportive white Southerners, and Northern transplants. They were opposed by "Redeemers," who sought to reestablish white supremacy and Democratic Party control in Southern government and society. Violent groups, including the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and Red Shirts, engaged in paramilitary insurgency and terrorism to disrupt the Reconstruction governments and terrorize Republicans.[3] Congressional anger at President Johnson's repeated attempts to veto radical legislation led to his impeachment, although he was not removed from office.

Under Johnson's successor, President Ulysses S. Grant, radicals passed additional legislation to enforce civil rights, such as the Ku Klux Klan Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1875. However, continued resistance from Southern Whites and the cost of Reconstruction rapidly lost support in the North during the Grant administration. The 1876 presidential election was marked by widespread Black voter suppression in the South, and the result was close and contested. An Electoral Commission resulted in the Compromise of 1877, which awarded the election to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes on the understanding that Federal troops would be withdrawn from the South, effectively bringing Reconstruction to an end. Post-Civil War efforts to enforce federal civil rights protections in the South ended in 1890 with the failure of the Lodge Bill.

Historians continue to debate the legacy of Reconstruction. Criticism focuses on the early failure to prevent violence and problems of corruption, starvation, and disease. Union policy is criticized as too brutal toward freed slaves and too lenient toward former slaveholders.[4] However, Reconstruction is credited with restoring the federal Union, limiting reprisals against the South, and establishing a legal framework for racial equality via the constitutional rights to national birthright citizenship, due process, equal protection of the laws, and male suffrage regardless of race.[5]

- ^ "The First Vote" by William Waud Archived February 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Harpers Weekly Nov. 16, 1867

- ^ "History & Culture - Reconstruction Era National Historical Park". U.S. National Park Service. www.nps.gov. February 24, 2023.

- ^ Rodrigue, John C. (2001). Reconstruction in the Cane Fields: From Slavery to Free Labor in Louisiana's Sugar Parishes, 1862–1880. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8071-5263-8.

- ^ Lynn, Samara; Thorbecke, Catherine (September 27, 2020). "What America owes: How reparations would look and who would pay". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Guelzo (2018), pp. 11–12; Foner (2019), p. 198.