Back Elektriese potensiaal AF የኤሌክትሪክ እምቅ AM كمون كهربائي Arabic Potencial llétricu AST Elektrisches Potenziäu BAR Электрычны патэнцыял BE Электрычны патэнцыял BE-X-OLD Електричен потенциал Bulgarian তড়িৎ বিভব Bengali/Bangla Električni potencijal BS

| Electric potential | |

|---|---|

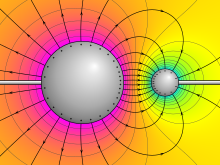

Electric potential around two oppositely charged conducting spheres. Purple represents the highest potential, yellow zero, and cyan the lowest potential. The electric field lines are shown leaving perpendicularly to the surface of each sphere. | |

Common symbols | V, φ |

| SI unit | volt |

Other units | statvolt |

| In SI base units | V = kg⋅m2⋅s−3⋅A−1 |

| Extensive? | yes |

| Dimension | M L2 T−3 I−1 |

| Articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

Electric potential (also called the electric field potential, potential drop, the electrostatic potential) is defined as the amount of work energy needed per unit of electric charge to move the charge from a reference point to a specific point in an electric field. More precisely, the electric potential is the energy per unit charge for a test charge that is so small that the disturbance of the field under consideration is negligible. The motion across the field is supposed to proceed with negligible acceleration, so as to avoid the test charge acquiring kinetic energy or producing radiation. By definition, the electric potential at the reference point is zero units. Typically, the reference point is earth or a point at infinity, although any point can be used.

In classical electrostatics, the electrostatic field is a vector quantity expressed as the gradient of the electrostatic potential, which is a scalar quantity denoted by V or occasionally φ,[1] equal to the electric potential energy of any charged particle at any location (measured in joules) divided by the charge of that particle (measured in coulombs). By dividing out the charge on the particle a quotient is obtained that is a property of the electric field itself. In short, an electric potential is the electric potential energy per unit charge.

This value can be calculated in either a static (time-invariant) or a dynamic (time-varying) electric field at a specific time with the unit joules per coulomb (J⋅C−1) or volt (V). The electric potential at infinity is assumed to be zero.

In electrodynamics, when time-varying fields are present, the electric field cannot be expressed only as a scalar potential. Instead, the electric field can be expressed as both the scalar electric potential and the magnetic vector potential.[2] The electric potential and the magnetic vector potential together form a four-vector, so that the two kinds of potential are mixed under Lorentz transformations.

Practically, the electric potential is a continuous function in all space, because a spatial derivative of a discontinuous electric potential yields an electric field of impossibly infinite magnitude. Notably, the electric potential due to an idealized point charge (proportional to 1 ⁄ r, with r the distance from the point charge) is continuous in all space except at the location of the point charge. Though electric field is not continuous across an idealized surface charge, it is not infinite at any point. Therefore, the electric potential is continuous across an idealized surface charge. Additionally, an idealized line of charge has electric potential (proportional to ln(r), with r the radial distance from the line of charge) is continuous everywhere except on the line of charge.

- ^ Goldstein, Herbert (June 1959). Classical Mechanics. United States: Addison-Wesley. p. 383. ISBN 0201025108.

- ^ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics. Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-81-203-1601-0.