Back استجابة الحكومات الأمريكية المحلية والولاياتية لجائحة فيروس كورونا Arabic وەڵامدانەوەی ویلایەت و حکومەتە ناوچەییەکانی ویلایەتە یەکگرتووەکانی ئەمریکا بەرامبەر پەتای جیھانی کۆڤید-١٩ CKB Confinamiento por la pandemia de COVID-19 en Estados Unidos Spanish Respons pemerintah lokal Amerika Serikat terhadap pandemi COVID-19 ID

This article needs to be updated. (June 2020) |

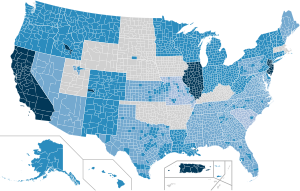

State, territorial, tribal, and local governments responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States with various declarations of emergency, closure of schools and public meeting places, lockdowns, and other restrictions intended to slow the progression of the virus.

Multiple groups of states formed compacts in an attempt to coordinate some of their responses. On the West coast: California, Oregon, and Washington state; in the Northeast: Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island; and in the Midwest: Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky.[1][2][3]

There was a link between public health outcomes and partisanship between states. At the beginning of the pandemic to early June 2020, Democratic-led states had higher case rates than Republican-led states, while in the second half of 2020, Republican-led states saw higher case and death rates than states led by Democrats. As of mid-2021, states with tougher policies generally had fewer COVID cases and deaths.[4][5] Thousands of US counties also initiated their own policy responses to the pandemic, resulting in significant variability even within states.[6]

- ^ "U.S. Midwest governors to coordinate reopening economies battered by coronavirus". Reuters. April 16, 2020. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "New York, California and other states plan for reopening as coronavirus crisis eases". Reuters. April 14, 2020. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ Sgueglia, Kristina (April 17, 2020). "7 Midwestern governors announce their states will coordinate on reopening". CNN. Archived from the original on May 31, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ VanDusky-Allen, Julie; Shvetsova, Olga (May 12, 2021). "How America's partisan divide over pandemic responses played out in the states". The Conversation. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Neelon, Brian; Mutiso, Fedelis; Mueller, Noel T.; Pearce, John L.; Benjamin-Neelon, Sara E. (July 1, 2021). "Associations Between Governor Political Affiliation and COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Testing in the U.S." American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 61 (1): 115–119. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.034. ISSN 0749-3797. PMC 8217134. PMID 33775513.

- ^ Ebrahim, Senan; Ashworth, Henry; Noah, Cray; Kadambi, Adesh; Toumi, Asmae; Chhatwal, Jagpreet (December 21, 2020). "Reduction of COVID-19 Incidence and Nonpharmacologic Interventions: Analysis Using a US County–Level Policy Data Set". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 22 (12): e24614. doi:10.2196/24614. PMC 7755429. PMID 33302253. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2020.