Back تبييض الشعب المرجانية Arabic Избелване на корали Bulgarian Blanqueig del corall Catalan Bělení korálů Czech Koralblegning Danish Korallenbleiche German Koralblankigo EO Blanqueo del coral Spanish سفیدشدگی مرجان FA Korallien vaaleneminen Finnish

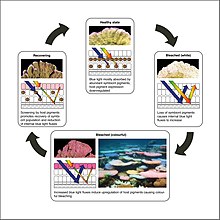

Coral bleaching is the process when corals become white due to loss of symbiotic algae and photosynthetic pigments. This loss of pigment can be caused by various stressors, such as changes in temperature, light, or nutrients.[1][2] Bleaching occurs when coral polyps expel the zooxanthellae (dinoflagellates that are commonly referred to as algae) that live inside their tissue, causing the coral to turn white.[1] The zooxanthellae are photosynthetic, and as the water temperature rises, they begin to produce reactive oxygen species.[2] This is toxic to the coral, so the coral expels the zooxanthellae.[2] Since the zooxanthellae produce the majority of coral colouration, the coral tissue becomes transparent, revealing the coral skeleton made of calcium carbonate.[2] Most bleached corals appear bright white, but some are blue, yellow, or pink due to pigment proteins in the coral.[2]

The leading cause of coral bleaching is rising ocean temperatures due to climate change caused by anthropogenic activities.[3] A temperature about 1 °C (or 2 °F) above average can cause bleaching.[3]The ocean takes in a large portion of the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions produced by human activity. Although this uptake helps regulate global warming, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in ways never seen before. [4] Ocean acidification (OA) is the decline in seawater pH caused by absorption of anthropogenic carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This decrease in seawater pH has a significant effect on marine ecosystems.[5]

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, between 2014 and 2016, the longest recorded global bleaching events killed coral on an unprecedented scale. In 2016, bleaching of coral on the Great Barrier Reef killed 29 to 50 percent of the reef's coral.[6][7][8][9] In 2017, the bleaching extended into the central region of the reef.[10][11] The average interval between bleaching events has halved between 1980 and 2016.[12] The world's most bleaching-tolerant corals can be found in the southern Persian/Arabian Gulf. Some of these corals bleach only when water temperatures exceed ~35 °C.[13][14]

Bleached corals continue to live, but they are more vulnerable to disease and starvation.[15][16] Zooxanthellae provide up to 90 percent of the coral's energy,[2] so corals are deprived of nutrients when zooxanthellae are expelled.[17] Some corals recover[1] if conditions return to normal,[15] and some corals can feed themselves.[15] However, the majority of coral without zooxanthellae starve.[15]

Normally, coral polyps live in an endosymbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae.[18] This relationship is crucial for the health of the coral and the reef,[18] which provide shelter for approximately 25% of all marine life.[19] In this relationship, the coral provides the zooxanthellae with shelter. In return, the zooxanthellae provide compounds that give energy to the coral through photosynthesis.[19] This relationship has allowed coral to survive for at least 210 million years in nutrient-poor environments.[19] Coral bleaching is caused by the breakdown of this relationship.[2]

- ^ a b c US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is coral bleaching?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "CORAL BLEACHING – A REVIEW OF THE CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2009.

- ^ a b "Corals and Coral Reefs". Smithsonian Ocean. 30 April 2018. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Turley, Carol (September 2011). "Ocean Acidification. A National Strategy to Meet the Challenges of a Changing Ocean: Book Reviews". Fish and Fisheries. 12 (3): 352–354. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00415.x.

- ^ Hall-Spencer, Jason M.; Thorndyke, Mike; Dupont, Sam (October 2015). "Impact of Ocean Acidification on Marine Organisms—Unifying Principles and New Paradigms". Water. 7 (10): 5592–5598. doi:10.3390/w7105592. hdl:10026.1/3897. ISSN 2073-4441.

- ^ "Coral bleaching on Great Barrier Reef worse than expected, surveys show". The Guardian. 29 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Gilmour, J. P.; Smith, L. D.; Heyward, A. J.; Baird, A. H.; Pratchett, M. S. (2013). "Recovery of an Isolated Coral Reef System Following Severe Disturbance". Science. 340 (6128): 69–71. Bibcode:2013Sci...340...69G. doi:10.1126/science.1232310. PMID 23559247. S2CID 206546394.

- ^ "The United Nations just released a warning that the Great Barrier Reef is dying". The Independent. 3 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Hughes TP, Kerry JT, Álvarez-Noriega M, Álvarez-Romero JG, Anderson KD, Baird AH, et al. (March 2017). "Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7645): 373–377. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..373H. doi:10.1038/nature21707. hdl:20.500.11937/52828. PMID 28300113. S2CID 205254779. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Mass coral bleaching hits the Great Barrier Reef for the second year in a row". USA Today. 13 March 2017. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Galimberti, Katy (18 April 2017). "Portion of Great Barrier Reef hit with back-to-back coral bleaching has 'zero prospect for recovery'". AccuWeather.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

When coral experiences abnormal conditions, it releases an algae called zooxanthellae. The loss of the colorful algae causes the coral to turn white.

- ^ Hughes TP, Anderson KD, Connolly SR, Heron SF, Kerry JT, Lough JM, et al. (January 2018). "Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene" (PDF). Science. 359 (6371): 80–83. Bibcode:2018Sci...359...80H. doi:10.1126/science.aan8048. PMID 29302011. S2CID 206661455. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Shuail, Dawood; Wiedenmann, Jörg; D'Angelo, Cecilia; Baird, Andrew H.; Pratchett, Morgan S.; Riegl, Bernhard; Burt, John A.; Petrov, Peter; Amos, Carl (30 April 2016). "Local bleaching thresholds established by remote sensing techniques vary among reefs with deviating bleaching patterns during the 2012 event in the Arabian/Persian Gulf". Marine Pollution Bulletin. Coral Reefs of Arabia. 105 (2): 654–659. Bibcode:2016MarPB.105..654S. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.03.001. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 26971815. S2CID 37407032.

- ^ Hume, Benjamin C. C.; Voolstra, Christian R.; Arif, Chatchanit; D’Angelo, Cecilia; Burt, John A.; Eyal, Gal; Loya, Yossi; Wiedenmann, Jörg (19 April 2016). "Ancestral genetic diversity associated with the rapid spread of stress-tolerant coral symbionts in response to Holocene climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (16): 4416–4421. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.4416H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1601910113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4843444. PMID 27044109.

- ^ a b c d "What is Coral Bleaching and What Causes It – Fight For Our Reef". Australian Marine Conservation Society. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Coral Bleaching". Great Barrier Reef Foundation. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Slezak, Michael (6 June 2016). "The Great Barrier Reef: a catastrophe laid bare". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b Dove SG, Hoegh-Guldberg O (2006). "Coral bleaching can be caused by distress to the coral. The cell physiology of coral bleaching". In Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Jonathan T. Phinney, William Skirving, Joanie Kleypas (eds.). Coral Reefs and Climate Change: Science and Management. [Washington]: American Geophysical Union. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-87590-359-0.

- ^ a b c Zandonella, Catherine (2 November 2016). "When corals met algae: Symbiotic relationship crucial to reef survival dates to the Triassic". Princeton University. Retrieved 13 September 2021.